|

The First Invasion of Quebec in the War of

1812

by Robert Henderson

Canadian Voltiguers and

Kahnawake warriors advance to border (Parks Canada)

While

war raged in the autumn of 1812 along Upper Canada’s Niagara frontier,

American forces continued to slowly gather south of Montreal on

Lake Champlain. After dithering most of 1812, an American army

left Plattsburgh, NY on November 16 heading towards the border.

Before departing one officer of the 2nd US Infantry penned a

letter that captured the mood and expectations of the troops:

This is perhaps the last time you will hear from me at this

place, if ever. We are preparing for a march, which will take

place in a few days. It is intended to make an attack on Lower

Canada [Quebec] immediately. We march without baggage or tents,

and everything we carry will be on our backs, and the Heavens

and a blanket our only covering, till we take winter quarters by

force of arms. Our force is very respectable, say 6 or 7

thousand, and all in high spirits. The fatigues we expect to

undergo will be equal to those experienced by our revolutionary

heroes, till we arrive at Montreal.”[1]

Another officer estimated the army’s strength at around 5,000

men and thought the target was the island fort of Isle aux Noix

on the Richelieu River.[2]

Arriving to take command of the “Grand Army of Canada”[3]

was Major-General Henry Dearborn. Nicknamed “Granny” by those

he commanded, Dearborn appeared determined to strike deeply into

Canada. Writing to the Secretary of War, Dearborn opined that

Montreal could be taken “with but little risk” and envisioned a

winter campaign against Quebec City.[4]

It was not the first time Dearborn was in a winter attack on

capital of Lower Canada. Almost to the day 37 years earlier, in

1775, a younger Dearborn had been part of a daring American

overland move from New England against Quebec City. This

attack ended unsuccessfully with Dearborn suffering from small

pox as a prisoner of war in the city he dreamed of conquering.[5]

Now in 1812, Dearborn was a much older man and attacks of

rheumatism dampened the 61-year-old General’s ambition. The

result was his poor health delayed invasion plans for more than

a week.

Major-General Henry Dearborn (Courtesy of the Art Institute of

Chicago)

On November 18, with his army concentrated on the

frontier at Champlain NY, Dearborn dispatched reconnaissance

parties across the border to gather intelligence on the enemy.

In charge of the “videts” or seers was Colonel Isaac Clark.

Clark was also a American Revolution veteran who had gotten the

nickname of “Old Rifle” for “rifling” through (pillaging) French

Canadian churches during that war. After reconnoitring and

skirmishing with Canadian light troops, Clark

returned at the end of the day to report that about 300 native

warriors were lurking within a few miles of the border. He also

reported a large force of Canadian regulars and militia were

stationed about ten miles down the road to Montreal. Lastly

Dearborn was informed that the roads leading into Canada had

been obstructed in numerous places by fallen trees.[6]

Natives, Canadian Voltigeurs, and

the Flank Companies of the 1st Battalion of Select Embodied

Militia skirmished with American advance parties south of

Lacolle River from November 18 to 22, 1812 (Parks Canada)

Preparing to meet the Americans was Major

Charles-Michel d'Irumberry De Salaberry of the newly-formed

Canadian Voltigeurs. Dressed in a green rifle-style uniform

trimmed with black mohair cording and dawning a unique bearskin

cap, De Salaberry was a professionally-trained light infantry

officer. He had served with the rifle battalion of the 60th

Regiment of Foot and the future father of Queen Victoria, the

Duke of Kent, had been his patron. De Salaberry had received

reports of the American advance the previous day and it was he

who had acted quickly to block the roads with abattis. The

Americans wildly overestimated the number of troops De Salaberry

had at his disposal. Instead of over two thousand, the French

Canadian Major had in fact only a few hundred men from his

regiment, the 1st Battalion of Select Embodied Militia, and some

Canadian Voyageurs stationed near the Lacolle River. In reserve eight

kilometres north of the Lacolle River were detachments of the

mentioned units along with the Canadian Fencible Regiment. While a

strict disciplinarian, De Salaberry could not be certain on how

the newly-formed Canadian Voltigeurs would fair in battle,

little alone the 1st Battalion of Select Embodied militia under his charge.

Charles-Michel d'Irumberry De Salaberry (Université de Montréal)

At least the Americans were right on the number of natives who

opposed them. Three hundred Mohawk warriors from Kahnawake,

south of Montreal, had answered the call to defend the

province. With the inclement November weather, the native

allies had set up camp on the north side of the Lacolle river.

About forty natives erected make-shift shelters to the left of

the bridge beside the Montreal road. Militiamen had also

constructed a crude log guardhouse among the native huts to

shelter the piquet patrolling that part of the river. With the

advance of the American army to the border, the bridge had been

wisely dismantled.

On the morning of November 19 Dearborn’s Adjutant

General issued orders that prepared his men for invasion: “the

General embraces the earliest opportunity to express his

confidence in the troops composing the army of the North. Their

bravery and patriotism will supply any deficiency in military

discipline and tactics which time and experience will render

perfect.”[7]

Not exactly a ringing endorsement of the army that was expected

to conquer Canada. Later that day, Dearborn’s invasion plan

received a setback. Militia officers informed the General that

no more than half of their men were willing to cross the

frontier into Canada.

Dearborn would later state to the Secretary of War

that, after meeting with his officers, it was decided that a

move on Montreal was no longer possible. According to Dearborn,

it was agreed that the army would remain a couple of days and

give the appearance of advancing, then return south to winter

quarters.[8]

However the General’s report to Washington appears dubious.

Dearborn had been slow and cautious throughout 1812 while he

built up what he considered to be an overwhelming force to take

Montreal. After Dearborn’s inaction and bragging about the ease

of taking Montreal, it is doubtful the General had abandoned his

quest for glory that day, contrary to what he later reported to

Washington.

While Dearborn’s enthusiasm for the campaign may

have been waning, one of his officers certainly was not. The

adventurous Colonel Zebulon Pike was chomping at the bit to

engage the enemy. Pike was well known at the time on both sides

of the border for his exploration of the West . This fame came

from his wildly popular published journals of his 1805-7

expeditions. Fighting the Shawnee in the Battle of Tippecanoe

in 1811 made Pike one of the few officers under Dearborn with

real experience countering native battle tactics.

Pike had spent months at Plattsburgh training his

regiment, the 15th US Infantry. Just before marching north, the

innovative Colonel embraced an experimental idea of equipping

part of his men with pikes:

Each subaltern is to carry a pike and a sword. The men are to

form three deep -- the tallest in the rear rank. The rear rank

have lately had their gun barrels cut off about 12 inches, and

not fitted for a bayonet. They are to be slung on the back,

when they proceed to a charge. The rear rank are to carry a

pike, somewhat of the form of a spontoon, attached to a pole 10

feet in length. Col. Pike thinks much of this kind of weapon,

while others condemn them.[9]

Scouting parties the previous day had reported an encampment at

the side of the road to Montreal on the north bank of the

Lacolle river. Pike persuaded Dearborn to allow him to attack

the enemy position there.

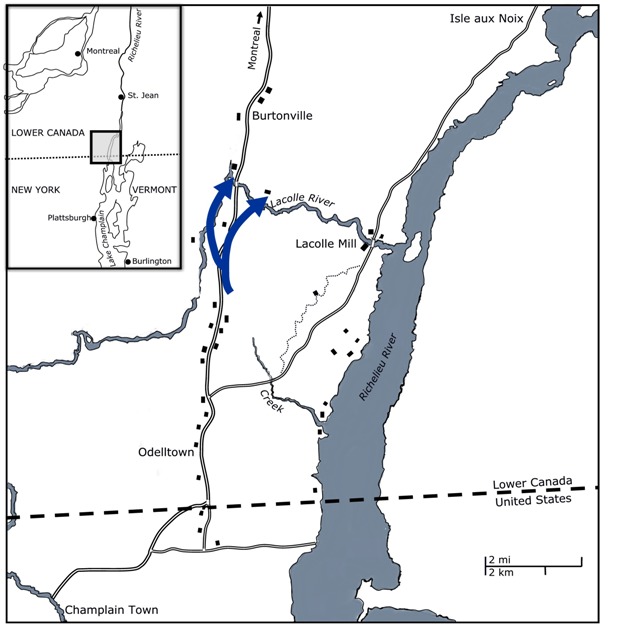

Map of the Lacolle Area and American

plan of attack. Left arrow represents Pike's Infantry

and the right arrow the 1st US Dragoons (Map: R Henderson)

On the night of November 19, Pike assembled his

regiment, and added volunteers from the militia under Major Melancton Smith and Major Guilford Young. Young of the Troy

Militia had already achieved the respect of his fellow officers

the previous month by capturing 40 Canadian Voyageurs at an

outpost near St. Regis. A troop of 1st Light Dragoons was also

added, bringing the strike force to between 600 and 850

effectives.[10]

While Pike was to attack the encampment, the Dragoons under the

guidance of Colonel Clark were to move against any enemy

stationed at a saw mill just east of the road. Pike’s plan was

to divide his infantry into two and encircle the guardhouse and

huts. He would lead most of the 15th US Infantry and Smith and

Young would direct the militia, which had been augmented by some

of his regulars.

Zebulon Pike (National Parks Service)

Pike’s preparations did not go unnoticed by the

prying eyes of British spies. While American militia volunteers

were being recruited, word of the planned attack reached the

ears of Prevost. The Governor General responded by dispatching

a hasty note the same day to De Salaberry warning him of a

possible attack:

If information can be relied on, the enemy will advance this day

from ChamplainTown. I have given directions for your support

from several points. You must keep them entangled in the woods

as long as possible. I rely on your best exertions.[11]

The message did not arrive in time. Still De Salaberry was

prepared: “The troops I had with me, have been laying in the

woods in the open air for ten days, always fully accoutred and

in momentary expectation of the enemy.”[12]

Constantly exposed to the November rain and cold the healthy

constitutions of the Canadians defending the border were slowly

chipped away at. One tired young French Canadian officer

of the 1st Battalion of Select Embodied Militia later wrote:

"After

five weeks to today (Nov 30) of continued hardships in the woods

of Canada ... I hope now to pass the winter quietly; for though

to serve one's country to the utmost of one's power and force,

be every one's duty, yet to serve it as I have done for five

weeks is very hard."

Canadian Voltigeurs on piquet duty

(Parks Canada)

Under the cover of darkness, Pike’s men quietly

exited their crude shelters of spruce boughs and moved out of

their Army’s encampment. As they crossed the border near Odelltown, it began to snow. For hours they trudged through the

snowy night, reconnoitring the swamps to the east of the road

for enemy pickets. After a brief rest for “regaling themselves

with potato whiskey and a good cheer from their commander” they

continued on through the darkness and cold. By then the snow

storm had subsided. The moon now helped light the rest of their

journey.[13]

At about 4 o’clock in the morning, Young’s Troy

Fusiliers and Smith’s militia volunteers were first to reach at

the banks of the narrow Lacolle River to the west of the road.

A native lookout was spotted and they moved to surprise him.

One witness recounted:

the Troy Fusiliers...crossed the river first, and proceeded down

the river, sometimes in the water and sometimes upon the bank,

about the distance of 40 or 50 rods, while a detachment of the

Pennsylvania regulars crossed and proceeded up the west side of

the point of land formed by a bend in the river, until they came

opposite to the Troy Fusiliers. All this manoeuvre was

performed wih the utmost silence, while every man had his eye

upon a poor Indian, the object of their pursuit.[14]

While in the process of relieving Native sentries stationed at

an oak tree that stretched across the river, 40-year-old Captain

William McKay of the Canadian Voyageurs “heard the enemy all

round him cocking their musquets.”[15]

McKay yelled loudly to warn the Native lookout of the impending

danger. The Americans responded with a “devil of a discharge”

of musket fire at McKay and his warriors.[16]

The Mohawk sentries jumped behind logs and trees, and, with

yells, returned fire. Hopelessly outnumbered, McKay retreated.

Mohawk warrior in Autumn by

Ron Volstad (Dept. of National Defence)

Meanwhile at the road, Pike’s men filed quickly into

the frozen waters of the shallow Lacolle river. By the time the

Americans climbed the rocky river bank, the Canadian militiamen

and native warriors housed at the guardhouse and shacks had

stealthily pulled out. So quick was the silent evacuation that

militia Captain Bernard Panet didn’t have a chance to lace his

shoes. The American troops under Smith and Young quickly swung

to the northern perimeter of the now deserted encampment, while

Pike’s force moved to close the trap by pushing from the south.

With visibility hampered by the darkness of the surrounding

woods of the early morning hour, the situation was ripe for

mistakes. The dangerousness of the moment was eloquently

summarized by Captain Jacques Viger of the Canadian Voltigeurs

who wrote: “In the night, all cats are grey.”[17]

The New York militia with Smith and Young entered

the small, lifeless shanty village searching for the enemy.

Large fires were burning but no one warmed themselves by them.

The Americans immediately entered the huts with fixed bayonets

expecting to catch a slumbering enemy unaware. Meanwhile Pike’s

men came up to the huts and guardhouse from the south right when

the New York militiamen were exiting the huts. Mistaking them

as the enemy, Pike’s force open fired. In response, Smith and

Young’s men discharged their arms and a devastating exchange of

friendly-fire ensued.[18]

The Natives urged on the folly with “horribly frightful yelling”

from the surrounding woods. So loud were the hoots and hollers

of the Kahnawake warriors that the Americans “imagined that

there were 4 or 500 Indians around them.”[19]

The fire-fight could be heard all the way back at

the American encampment in Champlain, New York. One officer of

the 16th US Infantry remembered:

When the firing of Colonel Pike’s party was heard, General

Chandler galloped into camp, exclaiming in a loud voice, “Where

is Colonel Pearse?” At that time, Colonel Pearce was lying under

a spruce brush, wrapped in a rug. He immediately arose, shook

the snow off, and ordered the troops to be paraded. As soon as

the cause of the firing was known, they were dismissed.[20]

After

five or six volleys Pike’s men realized their error and ceased.

The crude log guardhouse was torched and the Americans pulled

back empty-handed across the river.

With the native yells ringing in their ears, the

American withdrawal was rapid and disorderly. Meanwhile the US

Dragoons further east along the river torched some buildings and

then withdrew using a sawmill dam as a bridge to cross the

river. In the confusion, some of Pike’s men were taken as

prisoners. To speed their retreat, some soldiers threw away

their muskets and pikes. After carrying their wounded part of

the way through the snow, sleighs were commandeered to finish

the journey back across border. Later the Montreal Herald

mocked Pike’s misfortune by sarcastically naming the engagement

the “suicidal battle of River Lacolle”.[21]

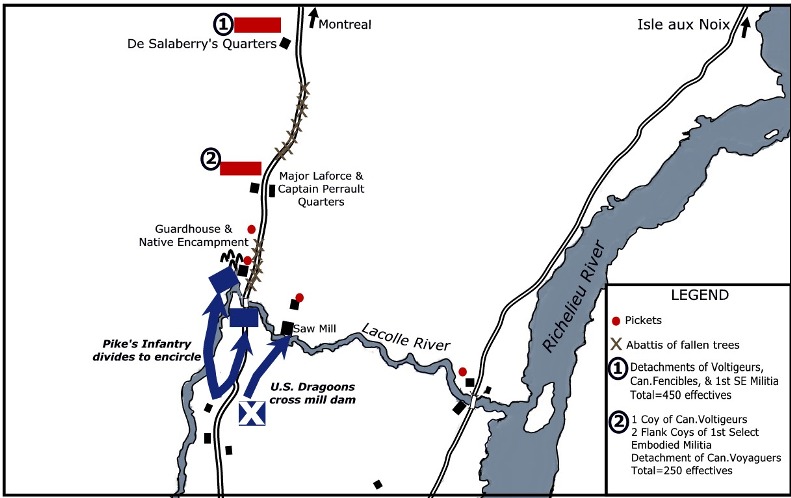

Map of Troop Positions and Movement,

November 20, 1812 (Map: R Henderson)

Captain McKay of the Canadian Voyageurs must have

taken particular pleasure at the news that Major Young was part

of the defeated American force. Young’s capture of Voyageurs at

St Regis a month earlier would have felt to a degree avenged.

In the daylight Lower Canadian troops were able to study

American armaments for the first time in the war:

The American muskets (we found many on the battlefield) are

strongly built and their barrel is fastened to the stock with

three large hoops of iron. Their bayonets, built like our, are

shorter and stronger. Their cartridge [musket round] contain

one bullet and three posts. We also found spears, the wood of

which is very long with a curved and sharpened spearhead.

[translation][22]

This was an accurate description of the US Springfield musket,

buck-and-ball musket rounds, and the 10 foot pikes of the 15th

US Infantry. The ferocity of the American volleys was also

evident. One militia officer noted “all the neighbouring trees

around being covered with bullets (one of our officers says that

he counted 20 balls in a space of about half a foot square).”[23]

American prisoner with Canadian Voltigeur and Mohawk warrior.

Display by

Militaryheritage.com

(photo: R Henderson)

Also during the following day, De Salaberry and

Major Pierre Laforce assessed the intent of Pike’s night-time

incursion into Canada. Evidence of it being a precursor to a

larger American offensive started to mount. Spies brought news

from the American camp that the army cooks had started to

prepare three days’ worth of soldier’s rations for the march.

Concluding this was a prelude to invasion, Laforce was ordered

to evacuate the local population. Knowing Dearborn’s army were

without camp equipage and intended to live off the land as they

advanced, Laforce was directed to herd local livestock north,

destroy any food supplies that could feed the invaders, and burn

any civilian buildings that could shelter Dearborn’s troops.[24]

On De Salaberry’s strategy, Prevost wrote “I approve the

precautionary measure you propose taking on the enemy’s

advance. Keep the cattle in your rear and make sure of whatever

you require for the troops, giving receipts on the Commissary

General, also for the hay you may destroy.”[25]

In effect, the Canadians had deployed the attrition strategy of

scorched earth.

With an early snow on the ground and plumbs of smoke

rising in the distance from Laforce’s grim work, Dearborn’s plan

for a late-season invasion was in tatters. Dysentery,

diarrhoea, measles and the first cases of typhus plagued the

General’s army and the plummeting temperatures were only making

the situation worse.[26]

Pike’s infectious zeal had not produced victory. Adding to his

painful attacks of rheumatism, “Granny” Dearborn had caught a

case of cold feet. The refusal of part of the militia to cross

the border offered Dearborn the excuse needed to abandon the

invasion. However the American troops under his command were

shocked at the decision. One officer recounted:

On the 22nd, at an early hour, we were ordered to cook three

days’ provisions. This order produced great joy - each regiment

supposing, of course, that Montreal was our destination. At. 10

o’clock AM when all was ready, our route was announced for

Plattsburgh, which occasioned much murmuring among the troops.[27]

However one American journalist took strange consolation in the

nature of Dearborn’s retreat:

That this expedition has ended with less bloodshed and disaster

than those of Detroit and Queenstown! And that his advance and

retrograde movements have not less merit than those recorded on

one of our allies, in this couplet of the poet:

‘A King of France with 20,000 men,

Marched up a hill, and then marched down again.’[28]

American Soldiers on the march. (pub. 1813)

So

ended the first invasion of Lower Canada. While militarily less

significant, Dearborn’s failure was greatly encouraging to the

population of Lower Canada. Dearborn had trumpeted the belief

of a disaffected French Canada unwilling to support Britain over

the United States. He had been proven wrong. The border had

been successfully defended by untested French Canadian troops

without any British assistance at all. For the next two

years Canadian units would be the primary protectors of the

province's border and contend with two more invading American

armies.

Today

The sleepy town of Lacolle now rests on the location

of the engagement that occurred in the early morning hours of

November 20, 1812. The town hall sits on the road to Montreal,

a stone’s throw from the bridge spanning the small Lacolle

River. The road to the U.S. border has not

changed much in 200 years and you can still cross into New York

State there. A history

interpretative centre has now been built in Lacolle to

commemorative the battle there, along with telling the rest of

the community’s story. The Battle on the Lacolle River in 1812

is often confused with the Battle of Lacolle Mill in 1814. Each

involved a mill, a wooden military structure, and a bridge

crossing the Lacolle River. However the battle in 1814 occurred

principally around a stone grist mill and log blockhouse on the

road running beside the Richelieu River. While the events

on the Lacolle River in 1812 were motivating to the Canadian war

effort, the spot has not yet been recognized as a National Historic

Site. This is likely do to the confusion with the battle

in 1814. It is hoped this research has removed this hurtle to

achieving this recognition.

As for the Canadian defenders involved in protecting

the province of Quebec that November, the history and heritage

of those regiments are now preserved by units of the Canadian

Forces through perpetuation:

|

1812 Unit |

Canadian Forces Unit |

|

Canadian

Regiment of Fencible Infantry |

Royal 22e

Régiment |

|

Provincial

Corps of Light Infantry (Canadian Voltigeurs) |

Les

Voltigeurs de Québec |

|

1st

Select Embodied Militia of Lower Canada |

Le Régiment

de la Chaudière |

|

Canadian

Voyageurs |

The Canadian

Grenadier Guards |

Regimental Colour of the 1st

Battalion of Select Embodied Militia. "1st Canadian Militia"

is painted on the colour. (Library and Archives Canada)

The

defence of Lacolle River is recognized as part of the "DEFENCE

OF CANADA 1812-1815" Campaign Honour, awarded to the units

of the Canadian

Forces listed above.

The

service of Kahnawake First Nation was also remembered recently

with the awarding of commemorative silver Chief’s medals by the

Governor General of Canada. Two hundred years ago, Chief’s

medals also conveyed friendship and gratitude from the

Government to the native peoples.

De Salaberry’s leadership at

Lacolle was commemorated in 1881 with

the erection in Chambly (Quebec) of a bronze statue to him, and

bearing the name “LACOLLE” on one side. Canadian Army

units played a prominent role in the project and the unveiling

ceremony. The memorial can be seen on the Canadian Forces

website by

clicking here. Also a small video on the monument

(en français)

can be found here. Along with his house being made a

National Historic Site and statues of him in both Quebec City

and Ottawa, De Salaberry was designated a person of national

significance in 1934. In addition communities have

been named after him including Salaberry and Salaberry-de-Valleyfield

in Quebec and De Salaberry in Manitoba, Also Salaberry Armoury

in Gatineau (Quebec) was named after him in 1938 for his

military service in the war, along with numerous streets in

Quebec and Ontario. His Voltiguers were also honoured by

the naming of streets in a number of communities, along with a

park in Drummondville (Quebec).

Je me souviens.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Gilles Pellerin, the

President de la Société

d'histoire Lacolle-Beaujeu

for his kind assistance and support in writing this

article. Mr Pellerin was the driving force behind

establishing an 1812 Interpretative Centre in Lacolle.

You can visit

the site here. Also my thanks

goes to André Gousse

for pointing out other ways De Salaberry and his Voltigeurs

canadiens have been commemorated.

[26]

James

Mann, Medical Sketches of the Campaigns of 1812,13,14.

(Dedham, 1816) p. 19.

|